A fierce wind and cold rain blew through the street in Portland, Maine, where Louisma Dosou, his wife and their two children huddled outside a shelter for families last week.

“They don’t have space for us,” Dosou, 40, said Wednesday morning. The family had been in the small coastal city about a week and still had no place to lay their heads. Every place they tried was full.

“We’ve slept in the street, at the airport,” he said, shaking against the gales coming off the Atlantic. “I am homeless. I don’t have a place to rest with my wife and children. They are sick, they have fevers.”

Dosou’s wife, Rodeline Celestine, covered their daughters, aged four and one-and-a-half, with a thin blanket as they crouched on a stoop behind Dosou. The girls wore socks in their little pink flip flops.

The family were among a group of asylum seekers who had stopped at the Chestnut Street Family Services shelter that morning before trying to find somewhere else to sleep later that night. One woman there was two or three weeks away from giving birth, her husband said.

Dosou and Celestine fled unrest in Haiti, travelling north from Brazil over the past three years in search of a safe new home. Their goal had been to reach Canada. Now, they are among the roughly 1,500 asylum seekers in Portland, population 68,000, where services are buckling under the needs of the growing number of migrants, many of whom had hoped to continue onto Canada.

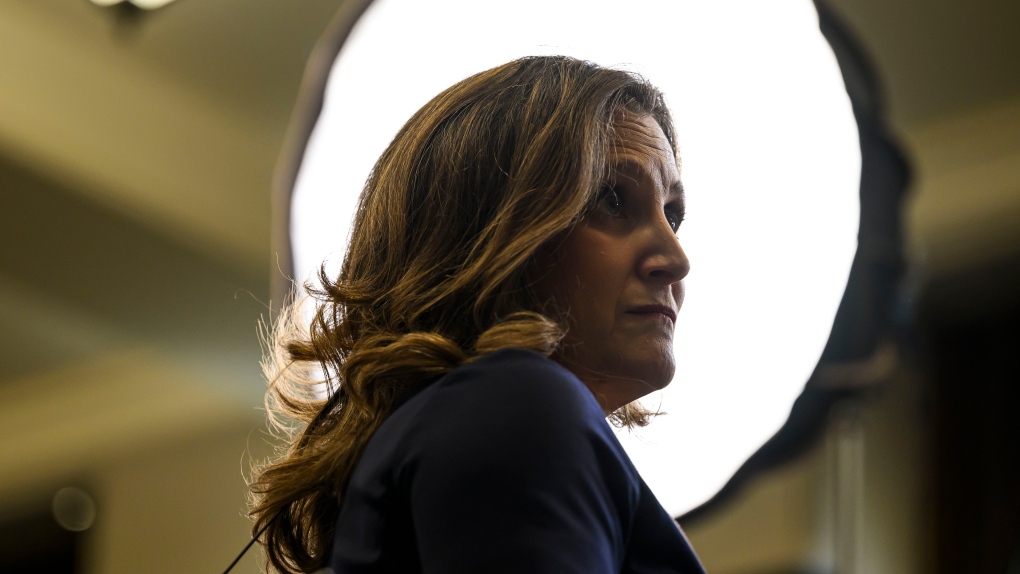

“We just cannot guarantee shelter anymore,” said Kristen Dow, director of health and human services for the city, which is about 230 kilometres southeast of the U.S. border with Quebec. Quebecers vacation at nearby beaches in summer.

Save for some exceptions, asylum seekers can no longer cross into Canada on foot, following changes to the Safe Third Country Agreement (STCA) with the U.S. earlier this spring.

Speaking in her office behind a waiting room filled with asylum seekers, Dow said the city and local organizations are using nearly every vacant space left to keep people from sleeping in the cold. Still, in recent weeks, Dow knows some have had to anyway.

She recalls a night in February when she got a call at 8:30 p.m. — both the family shelter and an overflow space with floor mats for 36 people were full — and there were 40 people waiting outside in the –10 C weather.

Dow asked if those 40 people could fit inside if workers picked up the mats and put everyone in chairs instead. “I said, ‘Then, let’s do that.’ There were children who were going to school and sleeping in a chair at night. I mean, that’s really heartbreaking to see,” she said.

In mid-April when the local basketball team’s season ended, the city set up 300 cots in their stadium, known as the Expo. Within a week it was full.

When CBC News visited the Expo last week, a crowd of about 20 gathered outside to speak with a reporter and photographer, asking when Canada would again let all asylum seekers in — saying their children were showing signs of malnutrition because they were only being fed bread, cakes and expired milk.

Nearly all of them said they had aimed to cross into Canada at Roxham Road, an unofficial border crossing straddling Quebec and upstate New York near Plattsburgh, a city 100 kilometres south of Montreal.

The crossing effectively shut down on March 25, after the STCA renegotiation closed a loophole that had allowed asylum seekers to simply walk across the border before turning themselves over to authorities. Quebec had been pressuring Ottawa to change the STCA, saying its resources were stretched thin after 40,000 people crossed at Roxham Road over the past year.

CBC News has been following the impacts of the closure, which left many asylum seekers stranded in the U.S.— after weeks, months or even years travelling through as many as a dozen countries to find a safe destination.

Portland was a popular stop on the way to Canada for French-speaking asylum seekers because of its small Central African community, the state’s history of refugee resettlement, and word that Mainers were kind and welcoming.

Since the STCA changes, “we’re not seeing people move on as much,” Dow said.

Alex Mbando, a 41-year-old Angolan father of four, clutched his one-year-old daughter Allegria outside the Expo.

“We heard Canada was looking for immigrants, but we arrive here and now they don’t want immigrants?”

Mufalo Chitam, the executive director of the Maine Immigrant Rights’ Coalition, an umbrella organization of 100 groups, says she was aware of 11 families who had arrived in the previous 24 hours. The coalition was working to have them sent to neighbouring municipalities that recently volunteered to help.

“We’re continuously trying to play catch up,” Chitam said in her office.

Dow and Chitam want to see more help and funding from the federal and state governments, and some support or collaboration from Ottawa.

And with the end of Title 42, the pandemic-era U.S. rule that blocked many migrants from crossing the southern border, even more people are expected to reach northern migrant destinations, including Portland, Chicago and New York.

Churches have allowed people to sleep inside, squeezing on and in between pews and in basements. Pastors of local African congregations have hosted numerous families in their homes. The soup kitchen at one of the Catholic churches has been serving more than twice as many people as usual, trying to stretch provisions to keep up with demand.

The Salvation Army has been sheltering 77 people, or roughly 20 families, on its gymnasium floor.

Mireille, a 39-year-old Congolese woman, has been sleeping there with her 12-year-old son since the winter.

She delayed their trip to the northern border after her 14-year-old nephew was detained at the U.S.-Mexico border.

“I regret staying here and I can’t go home because I fled my country and I can’t go back there,” she said. “How can we sleep like this? Every day, you wake up in pain.”

CBC News agreed not to use her last name because she feared repercussions to her safety or that of family members in Africa.

Exhausted children ran around her, their squeals echoing off the yellow cement walls. Outside, her son played with the other kids in the fenced parking lot. A boy, dribbling a basketball behind his back, said his dad told him that “when we have a house, he’s going to put me in a basketball team.”

Down the street, the small office of the Congolese Community Association of Maine fills up every day with asylum seekers looking to escape the wind and for assistance with their immigration files.

“At the end of the day, we have tears in our eyes because they can’t sleep here and we know they have nowhere to go,” said Mardochee Mbongi, the association’s president. Mbongi, 38, himself fled persecution in Congo in 2014 where he was a lawyer. He now works as a supervisor at a pharmaceutical manufacturer but took a six-week leave to deal with the migrant situation in Portland.

Similar scenes have been playing out in New York City and Chicago, which declared a state of emergency this week to request assistance from the National Guard to shelter migrants. Some 8,000 asylum seekers are said to be in Chicago, whose population is close to three million.

“Per capita, Portland, Maine, is sheltering more asylum seekers than just about any other city in the country,” Dow said.

The local library has been holding programs a few times a week allowing asylum seekers to print documents and use other services for free.

Sarah Skawinski, the library’s director of adult services, says that, while she and her colleagues are overwhelmed, she understands why Canada closed the STCA loophole.

“Sometimes you have to have boundaries to prevent everything from collapsing,” she said.

For Chitam, the head of the coalition, the situation is part of history. She arrived in Maine from Zambia after her husband got a U.S. green card in the early 2000s. She points to previous migration waves to Maine since the 1800s — the Irish, even the French-Canadians seeking temporary work who ended up putting down roots.

“Migration is not new. We just find ourselves in this era where it’s happening on our watch. So what do we do? We’re going to be part of history to respond,” she said.

History, and life, are said to come in circles, similar stories looping and coming back. But scars remain, like scratches on a record. Maxwell Chikuta, an entrepreneur whose many ventures include a small African grocery store, arrived in Portland 22 years ago from Zambia after fleeing civil war in Congo as a boy.

His story is one of success, but when this reporter asks how old he is, Chikuta’s voice catches. The truth is, he’s not exactly sure. His sister died in the war and their birth dates got confused.

He lifts his pant leg, revealing a shiny patch of skin where a stray bullet hit his shin as a child.

He’s not sure if he was eight or nine at the time.

Chikuta’s shop offers asylum seekers a piece of home. They can pick up cheap and filling fare, like corned beef and kwanga, a thick pastry made of cassava flour.

“It’s not just about selling food, it’s about mental health,” he said.

The migrants CBC News met in Portland said they would work to build a life in the U.S., but all said they hope to go to Canada. “If you told me [the border is] open right now, I would go. I’m ready. Will you bring me?” Mbando said.

A spokesperson for Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada says the STCA is now working “as it was originally intended” following the changes in March. Asylum seekers must file an official refugee claim either online or at a port of entry.

Canada said with the new border deal it would open 15,000 spots for immigrants from the Western Hemisphere, but still hasn’t given additional details.

But that option does not apply to many of those now in Portland.

For the others, it’s not known how long a refugee claim might take.

Over the next couple of days in Portland, there was no more sign of Louisma Dosou and his family.

CBC News was able to reach him later and learned that they had been taken to Sanford, a Maine city between Portland and Boston.

“Ça va bien,” Dosou managed through a poor phone connection, though he said they were still struggling to find food and a place to stay. The next day, he called to say an organization had found them a hotel room.

More Stories

‘Pretty scary’: Ill Ontario man stranded in Costa Rica finally recovering in Canada | Globalnews.ca

Trump allies Meadows, Giuliani among 18 indicted in Arizona election interference case | CBC News

RCMP confirm 2 kayakers missing from Sidney, B.C., found dead in Washington state | CBC News