In June 1940, the Second World War was not going well for Great Britain.

More than 300,000 Allied soldiers and sailors had just been rescued in the desperate evacuation from the French port of Dunkirk. The French army soon crumbled, and by mid-month German troops were marching into Paris.

The Nazi invasion of Britain seemed both imminent and inevitable.

The newly formed government of Winston Churchill needed a plan to keep the nation’s wealth out of Hitler’s hands. Some of it had already made its way across the Atlantic, but Britain needed a way to move the rest.

This is a story of tremendous courage on the part of many.– Tim Cook, Canadian War Museum

Operation Fish was hatched and would soon become the single-largest transfer of material wealth in history at the time — though very few people in Britain or Canada, where billions of dollars worth of gold and securities would be sent for safekeeping, ever caught a whiff.

“[It was] totally in secret. People just never knew about it, and all of those resources were there to prosecute the war in the event of a German invasion of Britain,” explained James Powell, an Ottawa historian and retired Bank of Canada executive who has researched and written about the daring wartime operation.

‘A load of fish’

Powell’s telling of the story begins with Sidney Perkins, an employee of the Bank of Canada’s Foreign Exchange Control Board. On the morning of July 2, 1940, Perkins left his home on Euclid Avenue in Old Ottawa South and arrived at work to learn he was being sent on a top-secret mission. The stakes were unimaginably high.

Later that day, Perkins and David Mansur, the bank’s acting secretary, met Alexander Craig from the Bank of England at Bonaventure Station in Montreal. The men shook hands and Craig announced he’d brought them “a load of fish.”

In fact, the heavily guarded train that had just arrived from Halifax contained no seafood. Instead, it held a nearly unfathomable amount of wealth in the form of gold and securities — the latter seized from the British public under the Emergency Powers Act.

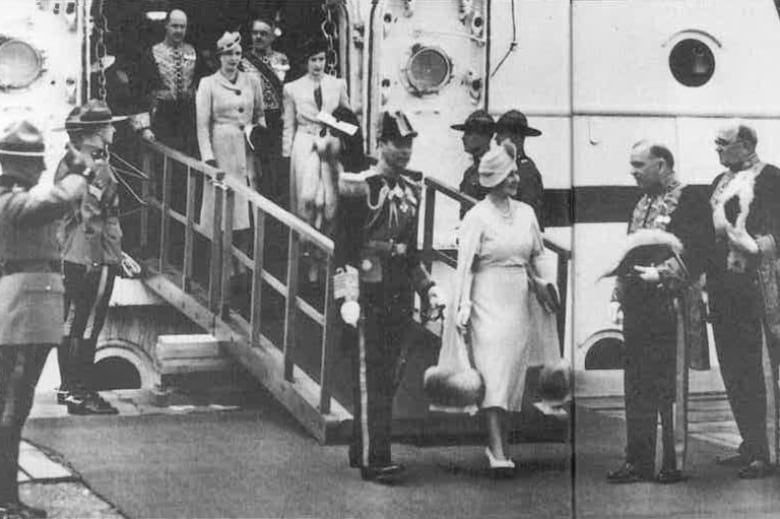

Craig and his “load of fish” had arrived in Halifax the previous morning aboard the light cruiser HMS Emerald following a harrowing seven-day voyage. A relentless gale had forced two destroyers escorting the shipment to turn back, leaving the Emerald and its precious cargo at the mercy of the U-boats that lurked in the North Atlantic. In the month of May alone, more than 100 Allied and neutral ships had been sunk.

For Britain, to lose a single vessel loaded to the gunwales with gold and securities would have been disastrous.

“To take the gamble and to ship all these resources over was truly a gutsy decision, to say the least,” Powell noted.

A desperate decision

Gutsy, but absolutely necessary. Britain needed free access to its own financial assets in order to buy much-needed materiel from the United States, which remained officially neutral at that time and as such was not allowed to extend credit for war supplies. It was strictly cash and carry. For Britain, losing that buying power would likely have meant losing the war.

“Britain isn’t moving the equivalent of hundreds of millions in gold because it’s an easy thing to do,” said Tim Cook, director of research at the Canadian War Museum and author of a dozen books on Canada’s military history. “They’re forced to do it because it really looks like Britain is going to fall.”

The shipment that arrived in Montreal on July 2 was split in two. Five-hundred boxes stuffed with securities then worth an estimated £200 million were taken to the Sun Life Building there, while the gold — some 9,000 bars packed into more than 2,000 bullion boxes, worth a total of £30 million at the time — continued on to Ottawa’s Union Station.

Under cover of darkness, armoured cars transported the treasure to the newly built Bank of Canada building on Wellington Street, where men worked in 12-hour shifts carrying crates and bags down to the bank’s 60-by-100-foot subterranean vault.

“The story that I have heard is that there was so much gold coming in at one point, they were just stuffing it everywhere, in hallways, in the incinerator room, just stuffing it to keep it safe before the accountants could come and look at all the boxes and tally it all up to make sure it was all there,” Powell said.

‘A cold chill’

That shipment paved the way for more, including a much larger convoy that left Britain just one week later.

“Seeing tens of millions in gold piled on the quay gave me a cold chill,” Perkins would later remark about one of the subsequent shipments he witnessed being unloaded in Halifax.

According to the Bank of Canada, some 1,500 tonnes of gold bullion and coins eventually made their way into the vault, where they remained for the duration of the war.

Powell estimates the value of all that gold at £470 million, the equivalent of nearly $90 billion Cdn today — making the Bank of Canada’s Ottawa vault the largest cache of gold outside Fort Knox. The value of the securities stored and traded by British bankers in Montreal is incalculable, Powell said.

So, too, was the value of Operation Fish to the Allied war effort.

“It was a bureaucratic act, but you can imagine if there had been an invasion of Britain, the Germans would have gone after all this gold and securities right away,” he said. “If that gold had been seized by the Nazis, who knows what the course of the war would have been?”

Mission remained a secret

Perhaps one of the most astounding aspects of Operation Fish is that while hundreds of Canadians were involved — including bankers, brokers, secretaries, labourers, guards and many others — it remained a secret until after the war. Not a single gold-bearing ship was ever lost, and not a single ingot was ever misplaced.

“Secrets are very hard to keep in times of war. Only one person talking could have set off a real chain of events here,” Cook said.

For Cook, Operation Fish stands as a testament to the “quiet professionalism” of the men and women involved.

“This is a story of tremendous courage on the part of many, of bureaucratic planning … the stuff that doesn’t usually get written about in histories, but really one of those key events that allows Britain to keep fighting,” he said.

“I believe that Canadians should understand this history. It’s part of what makes us who we are today.”

More Stories

Bob Cole, the play-by-play voice of countless NHL games, dies at 90 | CBC News

Green Party deputy leader given jail sentence for Fairy Creek old growth protests | Globalnews.ca

U.S. Supreme Court weighs extent of immunity for former presidents like Trump | CBC News