CBC Alberta and Saskatchewan have teamed up for a new pilot series on weather and climate change on the Prairies. Meteorologist Christy Climenhaga will bring her expert voice to the conversation to help explain weather phenomena and climate change and how it impacts everyday life.

When looking at our climate, we know our temperature is rising. Globally, annual mean temperatures have risen just over a degree since 1880.

In Canada, the warming has been more drastic.

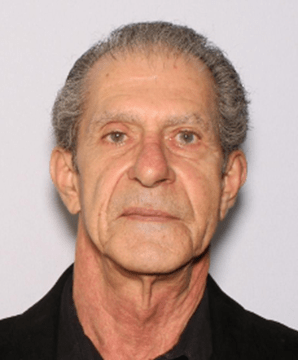

Nathan Gillett, a research scientist with Environment and Climate Change Canada, says the Arctic is warming at a faster rate due to ice melt and more heat being absorbed.

But so are the Prairies.

“Alberta and Saskatchewan have warmed by about 1.9 C since the mid-20th century,” Gillett says. “And they’re projected to continue warming at more than the global rate.”

According to Canada’s Changing Climate Report, this century the global climate will warm by a further 1 C in a low-emission scenario compared to a further 3.7 C in a business-as-usual high-emission scenario.

What does this warming mean for life in Alberta and Saskatchewan? Let’s take a closer look at what we expect to see in regards to our weather, water, and biodiversity.

Canada’s Prairies are already seeing more droughts, floods and warmer winters as the Earth’s climate warms, but what can we expect in the longer term? Meteorologist Christy Climenhaga breaks down the data. 2:29

Weather

With higher overall temperatures, you can expect shorter, warmer winters on average, with the occasional cold year.

Summers will get hotter with more severe heat waves.

With the change in temperatures, precipitation is expected to increase overall, but how and when it falls will be different.

“Globally and across Canada, as the atmosphere warms it can hold more moisture so that means we will increase in the most intense rainfall,” Gillett says. “Those big storms, the amount of rain that can fall with them, is projected to be larger in the Prairies.”

Ten-year-extreme daily precipitation, or those once-in-10-years events, could increase by 20 per cent in the high-emissions scenario versus five per cent in the low-emissions scenario, he says.

“More intense rainfall can drive urban flooding and increased runoff,” Gillett says. “The flooding in B.C. is an example of intense rainfall events.”

Scientists like Gillett continue to study those extreme weather events to prepare for the future.

“If we see a particular event, we know what impacts it had,” he says. “It makes it easier to understand the kinds of adaptations that we’ll need to take to reduce the damages associated with those kinds of events.”

Water

Though models indicate an overall increase in precipitation, future droughts and soil moisture deficits are projected to be more frequent and intense across the southern Canadian Prairies during summer by the end of the century under a high-emission scenario.

So how does that work?

When you look at the water supply chapter of our changing climate, timing is very important.

David Sauchyn, director of the Prairie Adaptation Research Collaborative at the University of Regina, is a lead author of a report detailing the changes we can expect in the Prairies as our climate warms.

Changes to the water supply will be the most consequential, Sauchyn says.

Precipitation will increase in the winter and spring, but will fall as rain, not snow, he says.

“Snow is the natural storage of water,” Sauchyn says. “We have really benefited from the fact that for three or four months of the year, the water stays around it doesn’t run off and, come springtime, we have this storage of water that replenishes our lakes, rivers and soil moisture.

“Many of the climate models indicate less precipitation in summer which is when we need it.”

And much of the rain we do see in the summer will be lost due to evaporation.

Another factor that will influence our water supply is the change in snowpack in the mountains.

“Most of the people in Alberta and Saskatchewan get their water from the Rockies,” Sauchyn says.

“Whether it’s river water derived from the mountains or soil moisture derived from rainfall, we will see less water in summer which is when we need it most.”

Biodiversity

What will this mean for our ecosystems and biodiversity on the Prairies?

“Prairie vegetation is extremely sensitive to temperature and moisture and timing of that,” says John Gamon, who uses remote sensing to study plant biodiversity at the University of Nebraska.

“You can get dramatic growth responses depending on temperature and moisture.”

Moisture is like a switch that can flip an ecosystem from one state to another, Gamon says.

Sauchyn’s report says as species respond to climate change, large regions of boreal forest could transition to aspen parkland and grassland ecosystems, while entire mountain ecosystems could disappear.

Sauchyn says that the trees in island forests in Saskatchewan such as Cypress Hills or Moose Mountain could also mostly disappear.

More grassland and less forest will profoundly affect wildlife in the prairies.

“Species have to adapt or they have to perish,” says Chrystal Mantyka-Pringle, a conservation planning biologist for the Wildlife Conservation Society of Canada.

She says that species are facing a cocktail of threats, including habitat loss, invasive species or environmental pollution.

“There are winners and losers,” Mantyka-Pringle says.

For example, wetland birds have increased by 30 per cent while birds of prey have doubled, she says.

“But a lot of other species are losing because they are more vulnerable to a warmer climate.

“We’ve seen a 60 per cent decline in grassland birds. We’ve seen the same decline in aerial insectivores which are the swallows, flycatchers and songbirds.

“There’s a global documentation on how insects are disappearing as well.”

Mantyka-Pringle says the loser species are those with slower reproduction systems making them slow to adapt, whereas the winners are the generalist species.

“They can move from one habitat to another,” she says. “So do we want a world where we see less species but more of them or a world where we have a diversity of wildlife?”

Invasive species also pose a risk, Mantyka-Pringle says. As our climate warms and becomes more variable we can expect to see new species.

“Winter ticks are moving further north and moose are struggling with the tick infestations,” she says. “So the changes aren’t just individual species, but it’s the community composition of different species and how they relate to each other.”

Erin Bayne, professor of biological sciences at the University of Alberta, says we are seeing more non-native species from the south moving north.

“They can be invasive and have negative effects on agriculture,” Bayne says. “For example, the white tail deer is not a native species to Alberta.

“It started spreading across Canada within the last 50 to 100 years. The only reason it can make it in Alberta is because the winter is warmer.”

Extreme weather events also affect wildlife as they become more frequent.

“The immediate mortality of animals from some of those events can have consequences to short-term population dynamics,” Bayne says. “It’s also destroying habitats for certain species.

“A thousand years ago these same kinds of events would be significant but the populations of animals would have been much larger. They would have been more resilient to this change.”

Our planet is changing. So is our journalism. This story is part of a CBC News initiative entitled Our Changing Planet to show and explain the effects of climate change and what is being done about it.

More Stories

China launches 3-member crew to its space station as it seeks to put astronauts on the moon by 2030

Giant prehistoric salmon had tusk-like spikes used for defence, building nests: study

Biden just signed a bill that could ban TikTok. His campaign plans to stay on the app anyway