TORONTO —

In a year chock full of vaccine innovation, researchers in Japan are trying a new tactic for a cholera vaccine: making it with genetically modified rice.

Researchers from the University of Tokyo and Chiba University published the results of their Phase 1 trial this week, which showed that their new vaccine candidate is well tolerated, and provided an immune response at all levels of doses.

Cholera is an infection that occurs when a person ingests food or water that is contaminated the bacteria vibrio cholerae. It can result in watery diarrhea and vomiting, and in severe cases, a person can die of cholera within days — or even hours — if they do not receive proper medical attention.

Although cholera is rare in Canada, it still affects millions of people worldwide. The World Health Organization estimates that there can be anywhere 1.3 to four million cases and 21,000 to 143,000 deaths caused by cholera each year.

While there are four cholera vaccines already that do not require needles, they require cold storage, a problem that researchers wanted to solve by creating a vaccine that could travel more easily.

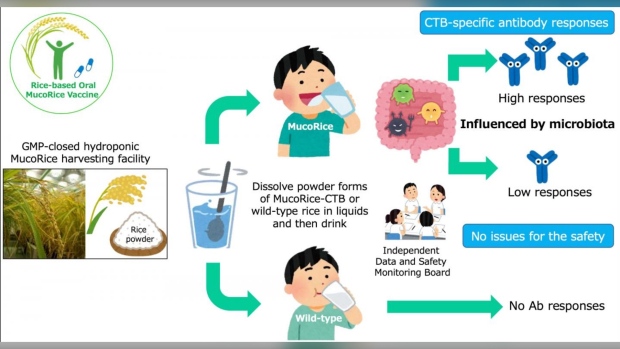

This new vaccine candidate, called MucoRice-CTB, is grown in genetically modified short-grain rice plants in isolated hydroponic farms. When the plants have matured, the rice is then ground into a powder and placed in aluminum packets for storage. To deliver the vaccine, the powder is mixed with a liquid for consumption.

The plants produce a “nontoxic portion” of something called cholera toxin b (CTB), which is a key part of how the toxin binds to target cells. This allows the body to build up antibodies against CTB.

“The rice protein bodies behave like a natural capsule to deliver the antigen to the gut immune system,” Professor Hiroshi Kiyono, from the Institute of Medical Science at the University of Tokyo, and the lead of the MucoRice project, said in a press release.

In the Phase 1 trial, 60 volunteers, all men aged 20-40 years, were given either a placebo or a dose of the vaccine at one of three dosage levels: 3 milligrams, 6 milligrams or 18 milligrams.

When the volunteers were tested two and four months after the vaccine, they found those who received the vaccine had developed antibodies, with those who received a higher dosage having developed the most antibodies.

“I’m very optimistic for the future of our MucoRice-CTB vaccine, especially because of the dose escalation results,” Kiyono said. “Participants responded to the vaccine at the low, medium and high doses, with the largest immune response at the highest dose.”

Around 11 of the volunteers had a low immune response, and researchers believe gut microflora has an impact on the outcome, as the MucoRice-CTB enters the body through the digestive system since it is ingested as a drink.

Volunteers who had a higher diversity of microflora tended to have a better response to the vaccine, researchers found.

“It’s all speculation right now, but maybe higher microflora diversity creates a better situation for strong immune response against oral vaccine,” Kiyono said.

Although some mild adverse events were reported, they were on par or less than the adverse events reported by those who received a placebo during the trial, suggesting the vaccine is safe.

More research is needed, but researchers are encouraged by the results of the Phase 1 trial, and plan to advance to more clinical trials in Japan and also overseas.

More Stories

Invasive strep: ‘Don’t wait’ to seek care, N.S. woman warns on long road to recovery | Globalnews.ca

Some Quebec hospitals are freeing up beds with virtual health care | CBC News

Improve balance and build core strength with this exercise