A graphic novel is bringing Saskatchewan’s history of LSD research alive.

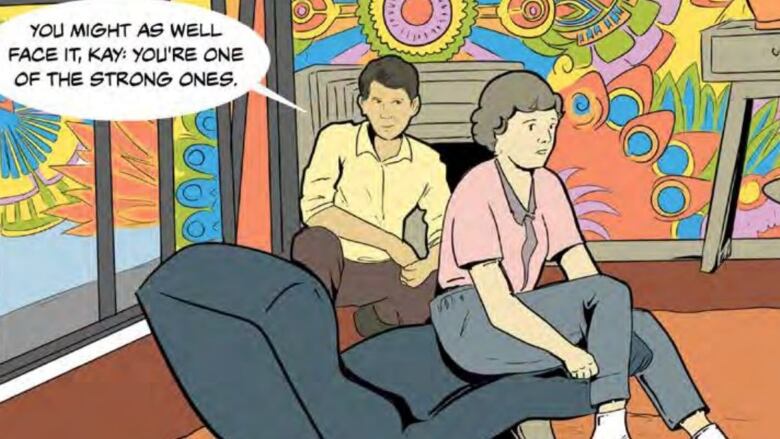

Wonder Drug: LSD in the Land of Living Skies uses comic book-style illustrations and text to depict groundbreaking research done in Saskatchewan during the 1950s involving the use of lysergic acid diethylamide — more commonly known as LSD — as a medical treatment for illnesses like depression and alcoholism.

The psychedelic was also used to gain a better understanding of what people with schizophrenia were experiencing.

The story follows Anglo-Canadian psychiatrist Dr. Humphry Osmond through his journey of psychedelic research, much of which was conducted at the Weyburn Mental Hospital or — at times — in his own living room.

The graphic novel was based on research done by Erika Dyck, a professor and Canada Research Chair in the History of Health and Social Justice at the University of Saskatchewan.

“It’s completely flattering and I feel very honoured to have been part of this process,” she said.

Dyck has been studying the history of psychedelic research in Saskatchewan for about 20 years, but it wasn’t until she moved from Saskatchewan to Ontario that she became interested in that history.

Saskatchewan Weekend13:24Wonder Drug: LSD in the Land of Living Skies

A brand new graphic book shines the spotlight on groundbreaking research that happened in Saskatchewan in the 1950s. University of Saskatchewan professor Erika Dyck is the researcher behind the book. She explains to host Shauna Powers some of the drug trials that happened in Saskatchewan during that time. 13:24

“When I was looking into these really exciting experiments that were done in a variety of places in Canada, I found this cluster of experiments in Saskatchewan,” she said.

“I was led back to my home province by a real interest in what was happening here in Saskatchewan in the 1950s as the province was engaged in reforms aimed at creating what we now know as Medicare and how that fit with these really exciting and cool therapies that were being explored in psychiatry.”

In the 1950s, Dyck said many medical professionals — including Osmond — were drawn to Saskatchewan “by the allure of what seemed to be a kind of research freedom.”

She said they could test new ideas and link them directly with policy reforms, work with interdisciplinary colleagues and “really sort of think outside of the conventional boundaries of modern medicine and science.”

‘Always something new around the corner’

Despite studying the works of Osmond for about two decades — along with meeting his children and grandchildren — Dyck said she still hasn’t learned everything about the psychiatrist.

“I am still utterly amazed as I keep learning new things about this man who I’ve read hundreds and hundreds of pages of records and documents about already, but there’s always something new around the corner.”

She said one characteristic that really stands out is his “dedication to trying to understand the plight of patients.”

Osmond felt that there was a disconnect between health-care providers — including psychiatrists — and patients who had been institutionalized for a long time and had trouble communicating what they were experiencing, according to Dyck, so he experimented with unconventional methods as a way to learn more about his patients.

“That really drove his research, so he wasn’t like some of the other psychedelic crusaders we might think of, like for him it [was] much more of a means than an end.”

LSD to treat alcoholism

The long and detailed history of LSD research in Saskatchewan has been documented in several books and hundreds of documents, but one of the main areas of focus was to see if LSD could be used to treat alcoholism.

Dyck said the results were sometimes remarkable, with some research groups claiming up to a 90 per cent success rate.

Success was measured on a number of factors, including sobriety and maintaining employment. Researchers also followed up with test subjects for up to two years, which included interviews with the test subjects’ wives — as most of them were men — to see how they were holding up.

As promising as the results were, they also raised suspicion.

“90 per cent was astounding,” said Dyck.

“There was a lot of criticism… because that seems kind of unbelievable. But I think part of it was a combination of finding people who would do well under these conditions, but also the kinds of supports that were available to maintain those follow ups, which were not insignificant.”

In other areas of LSD research, Dyck said experiments often involved people who worked at the Weyburn Mental Hospital such as students, psychiatric nurses, social workers, psychologists, psychiatrists and administrators — at least in the early stages of a trial.

Dyck said it was important for researchers to gain a deeper understanding of certain LSD experiences before experimenting with patients at the hospital.

Patients were involved in the next phase, but Dyck said “they always had someone present with the patient who had had their own LSD or mescaline experience so that there was a kind of empathetic guide.”

Psychedelic renaissance

Although some of the results appeared to be groundbreaking, LSD research came to a halt at the end of the 1960s as recreational use became a mainstay among the counterculture.

But a bad reputation in the public eye wasn’t the only reason LSD research ended.

“There was also pressure inside the, sort of, medical establishment,” said Dyck.

She said some people felt that LSD could be used as a single-dose therapy, which “didn’t fit with the sort of looming market opportunities for daily use therapies like antidepressant drugs that we might see on the market today, so I think there are twinned pressures here.”

As a result, public funding for the research eventually came to an end.

“I think it pushed some of that research underground. Some of it, of course, ended entirely,” said Dyck.

However, she said “some of those stories and some of the energy and inspiration” is starting to resurface, especially as ideas and technology around psychedelic research have changed — along with a current emphasis on mental health treatment and understanding.

“I think people are searching for alternatives once more. I think psychedelics represent that intellectual hope for thinking about something outside the box,” she said.

Dyck said using a graphic novel to share the history of LSD research can be a useful tool to talk about psychedelics and other drugs.

“I think it hopefully opens up this conversation to new audiences and provides a different pathway for thinking about how we engage in conversations about the safety and risk profiles of different drugs,” she said.

“There’s a lot of ground to cover here as we sort of move into what people are calling a psychedelic renaissance.”

More Stories

Apocalypse now: Why movie and TV fans love the end of the world | CBC News

I Don’t Know Who You Are is a visceral race against time for a critical drug | CBC News

From pop to politics, what to know as Sweden prepares for the 2024 Eurovision Song Contest